Nye publikasjoner

Forbedring av mitokondriene reverserer proteinakkumulering ved aldring og Alzheimers sykdom

Sist anmeldt: 02.07.2025

Alt iLive-innhold blir gjennomgått med medisin eller faktisk kontrollert for å sikre så mye faktuell nøyaktighet som mulig.

Vi har strenge retningslinjer for innkjøp og kun kobling til anerkjente medieområder, akademiske forskningsinstitusjoner og, når det er mulig, medisinsk peer-evaluerte studier. Merk at tallene i parenteser ([1], [2], etc.) er klikkbare koblinger til disse studiene.

Hvis du føler at noe av innholdet vårt er unøyaktig, utdatert eller ellers tvilsomt, velg det og trykk Ctrl + Enter.

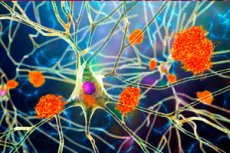

Det har lenge vært kjent at et kjennetegn ved Alzheimers sykdom og de fleste andre nevrodegenerative sykdommer er dannelsen av uløselige proteinaggregater i hjernen. Selv under normal aldring uten sykdom akkumuleres uløselige proteiner.

Til dags dato har tilnærminger til behandling av Alzheimers sykdom ikke adressert bidraget fra proteinuløselighet som et generelt fenomen, men har fokusert på ett eller to uløselige proteiner. Nylig fullførte forskere ved Buck Institute en systematisk studie av ormer som tegner et komplekst bilde av forholdet mellom uløselige proteiner i nevrodegenerative sykdommer og aldring. I tillegg viste arbeidet en intervensjon som kan reversere de toksiske effektene av aggregater ved å forbedre mitokondriehelsen.

«Funnene våre tyder på at det å målrette uløselige proteiner kan gi en strategi for å forebygge og behandle en rekke aldersrelaterte sykdommer», sa Edward Anderton, PhD, postdoktor i Gordon Lithgows laboratorium og en av de første forfatterne av studien publisert i tidsskriftet GeroScience.

«Studien vår viser hvordan det å opprettholde sunne mitokondrier kan bekjempe proteinaggregering forbundet med både aldring og Alzheimers sykdom», sa Manish Chamoli, PhD, postdoktor i laboratoriet til Gordon Lithgow og Julie Andersen, og en av studiens førsteforfattere. «Ved å forbedre mitokondriehelsen kan vi potensielt bremse eller reversere disse skadelige effektene, og tilby nye måter å behandle både aldring og aldersrelaterte sykdommer på.»

Resultatene støtter den gerontologiske hypotesen

Den sterke koblingen mellom uløselige proteiner som bidrar til normal aldring og sykdom støtter også et bredere bilde av hvordan aldring og relaterte sykdommer oppstår.

«Vi vil hevde at dette arbeidet virkelig støtter gerontologihypotesen om at det finnes en felles vei til både Alzheimers sykdom og aldring i seg selv. Aldring forårsaker sykdom, men faktorene som fører til sykdom oppstår veldig tidlig», sa Gordon Lithgow, PhD, Buck-professor, visepresident for akademiske saker og seniorforfatter av studien.

Det faktum at teamet fant et uløselig proteom i kjernen beriket med en rekke proteiner som ikke hadde blitt vurdert tidligere, skaper nye mål for forskning, sa Lithgow. «På noen måter reiser det spørsmålet om vi bør se på hvordan Alzheimers ser ut hos svært unge mennesker», sa han.

Utover amyloid og tau

Mesteparten av Alzheimers-forskningen så langt har fokusert på akkumulering av to proteiner: amyloid beta og tau. Men disse uløselige aggregatene inneholder faktisk tusenvis av andre proteiner, sa Anderton, og deres rolle i Alzheimers var ukjent. I tillegg har laboratoriet hans og andre observert at uløselige proteiner også akkumuleres under den normale aldringsprosessen uten sykdom. Disse uløselige proteinene fra eldre dyr, når de blandes med amyloid beta i et reagensrør, akselererer aggregeringen av amyloid.

Teamet spurte seg selv hva sammenhengen var mellom akkumulering av Alzheimers-aggregater og aldring uten sykdommen. Med fokus på amyloid beta brukte de en stamme av den mikroskopiske ormen Caenorhabditis elegans, lenge brukt i aldringsforskning, som hadde blitt genetisk modifisert for å produsere humant amyloidprotein.

Anderton sa at teamet mistenkte at amyloid beta kunne forårsake en viss grad av uløselighet i andre proteiner. «Vi fant ut at amyloid beta forårsaker massiv uløselighet, selv hos svært unge dyr», sa Anderton. De fant ut at det finnes en delmengde av proteiner som ser ut til å være svært sårbare for uløselighet, enten på grunn av tilsetning av amyloid beta eller under den normale aldringsprosessen. De kalte denne sårbare delmengden for «kjerneuløselig proteom».

Teamet demonstrerte også at kjernen i det uløselige proteomet er fylt med proteiner som allerede har blitt knyttet til en rekke nevrodegenerative sykdommer utover Alzheimers, inkludert Parkinsons, Huntingtons og prionsykdommer.

«Studien vår viser at amyloid kan fungere som en motor for denne normale aldersrelaterte aggregeringen», sa Anderton. «Vi har nå klare bevis, jeg tror for første gang, på at både amyloid og aldring påvirker de samme proteinene på lignende måter. Det er muligens en ond sirkel der aldring forårsaker uløselighet, og amyloid beta også forårsaker uløselighet, og de bare forsterker hverandre.»

Amyloidproteinet er svært giftig for ormene, og teamet ønsket å finne en måte å reversere denne toksisiteten på. «Fordi hundrevis av mitokondrielle proteiner blir uløselige både under aldring og etter amyloid beta-ekspresjon, tenkte vi at hvis vi kunne forbedre kvaliteten på mitokondrielle proteiner med en forbindelse, så kunne vi kanskje reversere noen av de negative effektene av amyloid beta», sa Anderton. Det er akkurat det de fant ved bruk av urolithin A, en naturlig metabolitt som produseres i tarmen når vi spiser bringebær, valnøtter og granatepler, som er kjent for å forbedre mitokondriefunksjonen: Det forsinket de toksiske effektene av amyloid beta betydelig.

«Det som var tydelig ut fra dataene våre, var viktigheten av mitokondrier», sa Anderton. Forfatterne sa at én konklusjon er at mitokondriehelse er avgjørende for den generelle helsen. «Mitokondrier har en sterk forbindelse til aldring. De har en sterk forbindelse til amyloid beta», sa han. «Jeg tror vår er en av få studier som viser at uløseligheten og aggregeringen av disse proteinene kan være en sammenheng mellom de to prosessene.»

«Fordi mitokondrier er så viktige for alt dette, er én måte å bryte nedgangssyklusen på å erstatte skadede mitokondrier med nye mitokondrier», sa Lithgow. «Og hvordan gjør man det? Tren og spis et sunt kosthold.»