Nye publikasjoner

Nytt molekyl etterligner den antikoagulerende virkningen av blodsugende organismer

Sist anmeldt: 02.07.2025

Alt iLive-innhold blir gjennomgått med medisin eller faktisk kontrollert for å sikre så mye faktuell nøyaktighet som mulig.

Vi har strenge retningslinjer for innkjøp og kun kobling til anerkjente medieområder, akademiske forskningsinstitusjoner og, når det er mulig, medisinsk peer-evaluerte studier. Merk at tallene i parenteser ([1], [2], etc.) er klikkbare koblinger til disse studiene.

Hvis du føler at noe av innholdet vårt er unøyaktig, utdatert eller ellers tvilsomt, velg det og trykk Ctrl + Enter.

Naturen har gitt flått, mygg og igler en rask måte å forhindre at blodet koagulerer, slik at de kan hente ut maten fra verten. Nå har et team av forskere ved Duke University oppdaget nøkkelen til denne metoden som et potensielt antikoagulantmiddel som kan brukes som et alternativ til heparin under angioplastikk, dialyse, kirurgi og andre prosedyrer.

I en artikkel publisert i tidsskriftet Nature Communications beskriver forskerne et syntetisk molekyl som etterligner effektene av forbindelser i spyttet til blodsugende skapninger. Det er viktig å merke seg at det nye molekylet også raskt kan nøytraliseres, slik at koaguleringen kan gjenopptas om nødvendig etter behandling.

«Biologi og evolusjon har utviklet en svært effektiv antikoagulasjonsstrategi flere ganger», sa seniorforfatter Bruce Sullenger, PhD, professor ved avdelingene for kirurgi, cellebiologi, nevrokirurgi og kreftfarmakologi og -biologi ved Duke University School of Medicine. «Dette er den perfekte modellen.»

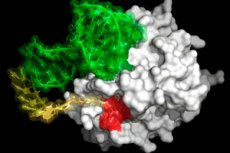

Sullenger og kollegene hans ved Duke University og University of Pennsylvania, inkludert hovedforfatter Haixiang Yu, PhD, et medlem av Sullengers laboratorium, startet med observasjonen om at alle blodsugende organismer har utviklet et lignende system for å hemme blodkoagulering. Antikoagulanten i spyttet deres bruker en tofaseprosess: Den binder seg til overflaten av spesifikke koagulasjonsproteiner i vertens blod og trenger deretter inn i proteinets kjerne for midlertidig å inaktivere koagulering mens de spiser.

De blodsugende organismene retter seg mot forskjellige proteiner blant de mer enn to dusin molekylene som er involvert i koagulering, men forskerteamet fokuserte på å utvikle molekyler som retter seg mot trombin og faktor Xa i menneskelig blod, og oppnår tofasisk antikoagulerende funksjon mot disse proteinene.

Den neste utfordringen var å utvikle en måte å reversere prosessen på, noe som er nødvendig for klinisk bruk for å sikre at folk ikke blør. Ved å forstå aktiveringsmekanismen fullt ut, var forskerne i stand til å lage en motgift som raskt reverserer koagulering.

"Vi tror denne tilnærmingen kan være tryggere for pasienter og forårsake mindre betennelse," sa Yu.

En annen fordel er at det er et syntetisk molekyl, i motsetning til den nåværende kliniske standarden de siste 100 årene, heparin. Heparin er utvunnet fra grisetarmer, noe som krever en enorm landbruksinfrastruktur som genererer forurensning og klimagasser.

«Dette er en del av min nye lidenskap – å forbedre kontrollen av blodpropp for å hjelpe pasienter, samtidig som vi tar hensyn til klimahensyn», sa Sullenger. «Det medisinske miljøet begynner å innse at det er et stort problem her, og vi må finne alternativer til å bruke dyr til å lage medisiner.»