Nye publikasjoner

Drømmer er forbundet med forbedret hukommelseskonsolidering og følelsesregulering

Sist anmeldt: 02.07.2025

Alt iLive-innhold blir gjennomgått med medisin eller faktisk kontrollert for å sikre så mye faktuell nøyaktighet som mulig.

Vi har strenge retningslinjer for innkjøp og kun kobling til anerkjente medieområder, akademiske forskningsinstitusjoner og, når det er mulig, medisinsk peer-evaluerte studier. Merk at tallene i parenteser ([1], [2], etc.) er klikkbare koblinger til disse studiene.

Hvis du føler at noe av innholdet vårt er unøyaktig, utdatert eller ellers tvilsomt, velg det og trykk Ctrl + Enter.

En natt tilbrakt med drømmer kan hjelpe deg med å glemme det hverdagslige og bedre bearbeide det ekstreme, ifølge en ny studie fra University of California, Irvine. Det nye arbeidet til forskere ved UC Irvine Sleep and Cognition Lab undersøkte hvordan drømmeminner og humør påvirker hukommelseskonsolidering og følelsesregulering dagen etter.

Funnene, som nylig ble publisert i tidsskriftet Scientific Reports, antyder en avveining der følelsesladede minner prioriteres, men alvorlighetsgraden reduseres.

«Vi fant ut at folk som rapporterer drømmer viser større emosjonell hukommelsesprosessering, noe som tyder på at drømmer hjelper oss med å bearbeide våre emosjonelle opplevelser», sa hovedforfatter av studien Sarah Mednick, professor i kognitiv vitenskap ved UC Irvine og leder av laboratoriet.

«Dette er viktig fordi vi vet at drømmer kan gjenspeile våre våkne opplevelser, men dette er det første beviset på at de spiller en aktiv rolle i å transformere våre reaksjoner på våkne opplevelser, prioritere negative minner fremfor nøytrale og redusere vår emosjonelle reaktivitet dagen etter.»

Hovedforfatter Jing Zhang, som tok doktorgraden sin i kognitiv vitenskap fra UC Irvine i 2023 og for tiden er postdoktor ved Harvard Medical School, la til: «Vårt arbeid gir de første empiriske bevisene for at drømmer er aktivt involvert i søvnavhengig emosjonell hukommelsesprosessering, noe som tyder på at det å drømme etter en emosjonell opplevelse kan hjelpe oss å føle oss bedre neste morgen.»

Studien inkluderte 125 kvinner – 75 via Zoom og 50 i søvn- og kognisjonslaboratoriet – som var i 30-årene og deltok i et større forskningsprosjekt som undersøkte effekten av menstruasjonssyklusen på søvn.

Hver økt startet klokken 19:30 for forsøkspersoner med en emosjonell bildeoppgave der de så en serie bilder som viste negative og nøytrale situasjoner (f.eks. en bilulykke eller et gressfelt), og vurderte hvert av dem på en ni-punkts skala for intensiteten av følelsene de fremkalte.

Deltakerne fullførte deretter umiddelbart den samme testen med nye bilder og bare et delsett av tidligere viste bilder. I tillegg til å vurdere sine emosjonelle reaksjoner, måtte kvinnene angi om hvert bilde var gammelt eller nytt, noe som hjalp forskerne med å utvikle en grunnlinje for både hukommelse og emosjonell respons.

Forsøkspersonene sovnet deretter enten hjemme eller på et av søvnlaboratoriets private soverom. Alle hadde på seg en ring som sporet søvn- og våkenhetsmønstrene deres. Da de våknet dagen etter, vurderte de om de hadde drømt natten før, og i så fall registrerte de drømmedetaljer og sitt generelle humør i en søvndagbok ved hjelp av en syvpunktsskala fra ekstremt negativ til ekstremt positiv.

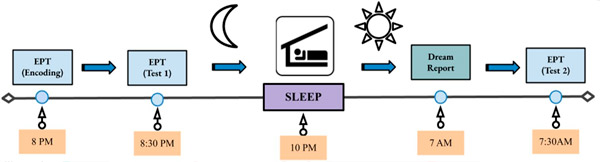

Studieprotokoll. Klokken 20.00 memorerte deltakerne bilder fra en EPT-oppgave (emosjonell bildeoppgave) og gjennomgikk deretter umiddelbar testing. Deltakerne sov deretter enten hjemme eller i laboratoriet, avhengig av om de ble testet eksternt eller personlig. Ved oppvåkning rapporterte deltakerne tilstedeværelsen og innholdet i drømmene sine og gjennomgikk forsinket EPT-testing. Kilde: Scientific Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-58170-z

To timer etter at de våknet, gjentok kvinnene den andre emosjonelle bildeoppgaven for å måle hukommelsen og reaksjonene deres på bildene.

«I motsetning til typiske søvndagbokstudier som samler inn data over flere uker for å se om dagtidsopplevelser dukker opp i drømmer, brukte vi en studie over én natt som fokuserte på følelsesladet materiale og spurte om drømmegjenkjenning var assosiert med endringer i hukommelse og emosjonell respons», sa Zhang.

Deltakerne som rapporterte drømmer husket negative bilder bedre og reagerte mindre på dem enn nøytrale bilder, noe som ikke var tilfelle for de som ikke husket drømmer. I tillegg, jo mer positiv drømmen var, desto mer positivt vurderte deltakeren negative bilder dagen etter.

«Denne forskningen gir oss ny innsikt i drømmers aktive rolle i hvordan vi naturlig bearbeider våre hverdagsopplevelser, og kan føre til tiltak som øker drømmerytmen for å hjelpe folk med å takle vanskelige livssituasjoner», sa Mednick.